A simplified and feature post-styled version of this article was published in The Record Nepal

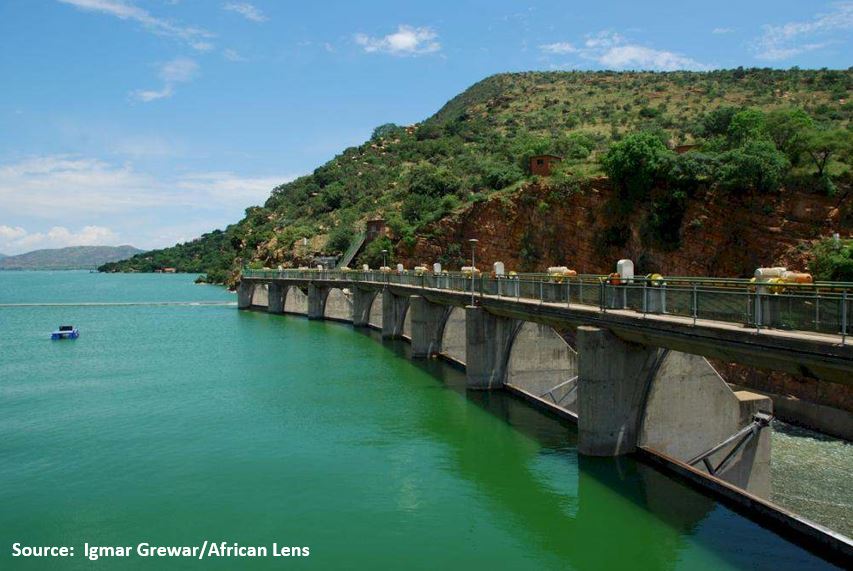

Damming of river systems has been historically observed as the key infrastructural gateway to enable human progress in the last centuries. In a nutshell, dams have allowed modern societies to achieve food security, energy security, and other advancements in infrastructure technology that has significantly contributed towards improved living standards and quality of life of the general population. Hence, human civilization has encouraged damming of almost all major river systems and tributaries across both hemispheres of the world to impound and divert natural courses of water to supply large irrigation & drinking water projects, control floods, and produce significant amounts of electricity to power industrial development and modern lifestyles.

National Geographic reports two-thirds of the major river systems of the world to have been already dammed for various purposes by 2019 amid the global dam race to build dam infrastructures. Meanwhile, the Hydropower Status Report 2020 of the International Hydropower Association (IHA) reports total global hydropower capacity has already reached 1,308 gigawatts (GW) by the same year. But the actual intensity of the damming activities across the river systems of the world can be most accurately pictured by a research letter published as early as 1995 that estimated reservoir systems behind dams to have already impounded as much as 10,000 cubic kilometers of water, equivalent to five times the volume of water in all the rivers of the world. This amount of water impoundment is estimated by the research to have likely caused a measurable impact on the earth’s rotation, the tilt of the axis, and the shape of its gravitational fields.

Environmentalists and scientists, until today, have discovered several impacts of dam infrastructures on river geomorphology, aquatic ecosystem, and larger riparian & floodplain ecosystems consisting of terrestrial biodiversity and indigenous settlements. Patrick McCully, in his book Silenced River: The Ecology and Politics of Large Dams, identifies many dams such as Balbina Dam, Brokopondo Dam, Aswan High Dam, and Akosombo Dam to have caused notorious ecological impacts in the form of massive inundation of the riverine & floodplain biodiversity hotspots and habitat, intensive alteration of river microbiota, and coastal erosion in tropical environments. These dams are also recognized to have inundated the most hectare of terrestrial & wetland biodiversity and displaced the greatest number of populations per Megawatt of electricity generated as per the World Bank report published in 2003. A similar observation was also made recently in the context of the newer dams such as the Lower Sesan 2 Dam that dams another major tropical tributary downstream of the Mekong River recognized to be the current hotspot of dam-building activity. These revelations paint a worrying consequence of large dams that contrasts the popular perception of dams as the clean and green intervention to economic growth and sustainable development.

Ecological impacts of dams installed in the mountainous physiography of Nepal

The nature of the ecological impacts of dam projects majorly depends on the physical geography of the locations where the dams are installed and the type & purposes of the dams in general. Specifically, in the context of Nepal, river dams have been majorly installed on the upstream regions of the snow-fed river systems located in the high and middle mountain physical zones featuring vegetation above the sub-tropical climate. The dams have been constructed mainly to generate hydroelectricity through Run-of-the-River (RoR) generation systems that do not maintain reservoirs and depend on fast-flowing waters of high-gradient river sections to run turbines. The mountainous geographical feature where the portfolio of hydroelectric dams is located in Nepal along with the specific type of generation mechanism that is feasible based on topographical limitations and opportunities provided generate ecological impacts that are dissimilar in type or intensity from commonly observed impacts of dams hosting large reservoir systems often with flood control purpose other than electricity generation. Hence, a diagnosis of the impacts of damming rivers at steeper gradients in the mountainous physiography of Nepal can contribute to understanding how the specific type of dam infrastructures currently built in the mountainous environment uniquely impact the local ecological and social scene.

River damming and the Issue of terrestrial land cover submergence

A study on the impacts of hydroelectricity projects on apex wildlife predators reports that hydroelectricity dams built in steeper topography tend to produce equivalent amounts of power without occupying large ecological footprints, thereby having smaller impacts per unit of electricity generated than projects developed in tropical flatlands. Pravin Kumar, serving in the capacity of water resource engineer for the Ministry of Energy, Water Resource, and Irrigation (MoWRI) of Nepal, affirms that dams built in steeper topography dominated by mountain reliefs limits upstream ecological impacts in the form of inundation of riverine ecosystem, biodiversity, and habitat primarily because of the practice of flooding very limited area of land per megawatt of electricity generated in ROR projects in comparison to hydroelectricity dams with reservoir facilities. The mere size of head ponds behind the dams of the ROR projects in Nepal which is multiple times smaller than reservoir systems of storage-type projects is also the reason behind such projects in Nepal have only minimally affected the riparian ecosystem and local habitats due to inundation of terrestrial land cover, says Balaram Bhattarai. Bhattarai, serving in the capacity of the senior environmental officer at Hydro-Consult Engineering Limited, also confirms that the formation of head ponds behind the dams of ROR projects built at high and middle mountain physiography has yet not required mass involuntary resettlement of the local riparian population to submerge former settlements.

However, ROR hydroelectricity projects installed in the mountainous landscape of Nepal suffer from the technical disadvantage of having to completely rely on the variability of the natural flow rate of the rivers which affects the ability of the projects to generate electricity consistently. Kumar confirms that the absence of reservoir systems behind dams of ROR-type projects leaves the system vulnerable to the issue of variability, whereby the magnitude of the impact of change in flow rates amplifies the generation instability. In the meantime, experts expect more variability in the hydrological flow regimes of the perennial snow-fed rivers of the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH) owing to the impact of Climate Change that adds further stress to ROR projects installed in the mountain physiography of Nepal to maintain consistent electricity generation. Kumar recognizes the limitation of generation instability for ROR-type hydroelectricity projects to be a significant reason for the government and power producers in Nepal to have pledged for reservoir-type systems in lower geological belts in near future.

Issue of Eutrophication, Salinization, and thermal stratification

Eutrophication is another major issue that troubles large reservoir systems that worsen the chemical and physical properties of the huge amount of lacustrine or still water stored behind dams. It is a phenomenon that occurs in reservoir systems mostly due to the mass decomposition of the inundated terrestrial vegetation that causes a considerable release of non-synthetic Greenhouse Gases (GHGs) such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (MH4). The phenomenon also drastically depletes the level of Dissolved Oxygen (DO) in the reservoir water while increasing the level of foul-smelling Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S) known to be hazardous to human health. Meanwhile, the enrichment of nutrients following the phenomenon of massive underwater decaying also causes phototrophic organisms to proliferate (algae bloom) at the surface of the reservoir water.

This change in the physical and chemical composition of the reservoir water involving increased level of nutrient load and decreased level of dissolved oxygen particularly sever the survival rate of endemic fish species and benthic macroinvertebrates and facilitates invasion of the local aquatic environment by the exotic fish species and non-native biota. The entire process of eutrophication also results in the accumulation of dangerously high levels of mercury in fishes as they intake bacteria that transform originally harmless inorganic mercury present in decomposing matter into methylmercury (CH3Hg) toxic to the central nervous system of humans. It is important to note that the deteriorative change in aquatic biodiversity and ecosystem can spread tens of kilometers or more below the dam as the altered reservoir water eventually connects with the downstream aquatic environment.

Research concerning the identification of the process and occurrence of eutrophication suggests that the phenomenon is often acutely prevalent in dams supporting large hydroelectric reservoirs in tropical forests. The worst of which was observed in Brokopondo Dam only 72 meters above sea level in Suriname, whereby the massive emission of Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S) in the reservoir required workers to wear masks for two years after the reservoir started to fill. However, water in a small head pond behind a run-of-river dam is known to undergo very little or no chemical or physical deterioration as such. Speaking of which, Gauri Shankar Conservation Area Project (GCAP) field officer Pramod Regmi who has been involved in monitoring the ecological and wildlife impacts of built construction in the conservation area is not aware of the eutrophication phenomenon in the head ponds behind ROR dams within the periphery of the protected zone that hosts several ROR hydroelectricity projects including the Upper Tamakoshi Hydroelectric Project (UTKHEP) with the largest installed capacity in Nepal. Regmi speculates that the vegetative land cover, temperature, and climate above the sub-tropical belt in which the ROR hydroelectricity projects in Nepal are mostly located may not be favorable for the process of eutrophication to occur in head ponds behind dams. Meanwhile, Bhattarai believes the phenomenon of eutrophication has not remained an environmental concern for ROR projects in Nepal also because waters in the head ponds are not stored or kept still until long enough for the process of eutrophication to occur. While the still water or lacustrine phenomenon in the head ponds behind dams is permanent, the water that forms the pond itself turns over very frequently in comparison to that of reservoir systems.

On the same note, the current environmental mandates also do not recognize the eutrophication of head ponds as a probable environmental concern and therefore do not warrant measures to prevent and control the issue during the construction and operation of hydroelectric projects. Bhattarai confirms that tests for the physical and chemical parameters of the river water that also measure the level of Dissolved Oxygen (DO) in the water are however conducted during the phase of environmental assessments before the construction of the project. But periodic monitoring of such parameters that rather helps in recognizing the phenomenon of eutrophication in the river system above and below the dam during the operational phase of the project is not guaranteed.

Similar remarks are also made in regard to the issue of salinization of reservoir water most commonly observed in the tropical and coastal environment due to evaporation of the exposed surface water of the reservoir to heat and sunlight. Kumar believes that the ecological issue of salinization is unlikely in head ponds behind ROR dams in Nepal because the stored water is purely composed of freshwater originating from the mountain glaciers or cryosphere, and is at least not immediately connected to the saltwater of the oceans as commonly observed for river systems belonging to tropical environments. However, not much scientific research has been conducted yet to understand the issue of salinization of head ponds formed above sub-tropical belts. Regardless, the issue of reservoir salinization has remained a severe problem for major river systems across the globe with large cascading reservoir dams including the Colorado River known to be the lifeline of the Southwestern United States of America (USA). Increased salinity of the reservoir systems owing to evaporation of reservoir water is known to increase soil salinity affecting agricultural productivity in the river basin, affecting surface and groundwater quality making it unfit for drinking and other household purposes, and disturbing freshwater ecosystem and biodiversity.

Meanwhile, there are other ecological impacts of reservoir systems that are simply attributable to the conversion of naturally flowing water into still water with the help of permanent anthropogenic interventions such as dams. Since flowing (lotic) water environments such as rivers and streams are hydrologically different to still (lentic) water environments such as lakes, ponds, and oceans, imposing still water dynamics into a flowing water environment is bound to alter the hydrological property of a river system with considerable implication to the aquatic system accustomed to flowing water regime. In such context, installing a dam across naturally flowing river systems to create a large pool of still water behind them causes the lower (hypolimnion) level of the stored water to become anoxic (or depleted of dissolved oxygen) and cooler in comparison to the upper (epilimnion) level due to the thermal stratification of reservoirs. A such phenomenon involving reductions in oxygen levels and changes in water temperature below a certain height of the stored water severely disturbs the lifecycle of freshwater aquatic organisms comprising of breeding, hatching, and feeding activities dependent on thermal cues. Moreover, the impact is also observed in the downstream aquatic ecosystem whilst the cooler and anoxic water from the bottom of the reservoir is discriminatively channeled to the penstock to ensure maximum water pressure.

Bhattarai confirms that the tests for still water thermal stratification of head ponds behind hydroelectric dams or measures to prevent the impact of such phenomenon in downstream river systems are neither undertaken by the power producers nor required by the environmental regulation in Nepal. Bhattarai instead claims that thermal stratification of head ponds behind ROR dams is unlikely for the same reason it is unlikely for head ponds to eutrophicate. As such, water in the head ponds behind dams is not kept still long enough for it to thermally stratify at different depths of the pond. However, Kumar finds thermal stratification to be a prevailing ecological issue for multiple river diversion projects being pledged across the length of the country to facilitate surface water irrigation systems for agricultural lands in the southern belt of Nepal. Kumar argues that any abrupt change in the river temperature of the target river systems following the anthropogenic diversion of another river system with different thermal dynamics into the target river will adversely impact the endemic aquatic ecosystem below and above the artificial confluence.

Issue of sediment trapping and its implications

Although scientifically untested, statements from dam engineers and conservationists imply that the ecological impact of dams as the result of the formation of reservoir systems may be theoretically unfounded or minimally pronounced in the case of dams supplying ROR hydroelectricity projects in Nepal with mere head ponds instead of larger reservoir systems. However, the same cannot be implied for a widely recognized set of ecological implications of dams that are attributed to creating a divide between a flowing river that disturbs the flow and migration of various elements crucial to the river ecosystem and biota apart from water.

In such context, sediment trapping is a popular phenomenon that follows damming of river systems whereby sedimentary matters such as gravels, rocks, cobbles, and soils that form and sustain the geomorphology of the river beds and channels are unable to flow downstream due to blockage of the passage by the dams. Sediment trapping deprives downstream river systems of sediments that cause geomorphological deterioration of downstream river beds, channels, and floodplains with a visible impact on the river and riparian ecosystem. This phenomenon accelerates the incision of river beds and narrows river channels, resulting in disfiguration and deterioration of the river.

Kumar has witnessed this phenomenon occurring in multiple river beds in Nepal during his canal surveys for irrigation projects. Kumar particularly identifies the impact of river bed incision to severe the status of groundwater and aquifer systems that depends on the surface water of the flowing river to recharge. As the height of the river beds falls below a certain level due to bed incision, the surface water of the river becomes unable to contribute to the groundwater system thus causing a simultaneous drop in the water table. Kumar believes that the occurrence of river system incision due to dam building and river bed mining activities is severely affecting the groundwater regime of the Terai and Churegeological belts that heavily depends on snow-fed surface water systems flowing from the upper and middle mountains belts for aquifer recharge. Today, groundwater depletion is commonly observed in the southern belt of the country also owing to disruption in the linkage between ground and surface water systems due to anthropogenic interventions. However, the monitoring and management of groundwater and aquifer systems in Nepal is still in its infancy. Meanwhile, a comprehensive assessment report prepared by International Cooperation for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) sights a significant lack of data concerning hydrogeological characteristics and spatial distribution of aquifers in the HKH region including Nepal to support policy decisions. Meanwhile, whatever of the limited available data is yet to surface in the policy decisions and practices of the governments in the federal arrangement of the country.

River bed incision or erosion also diminishes the ability of the river to support aquatic and terrestrial biodiversity within the river and riverine ecosystem. For instance, erosion of sedimentary cover in river beds limits the ability of the river to support the freshwater aquatic lifecycle and ecosystem such as the spawning ability of fishes and other benthic macroinvertebrates that require gravel and soil to provide necessary spawning grounds. Likewise, sediment entrapment behind dams also limits the flushing of soil nutrients such as Silica (SiO2), Phosphorus (P4), Nitrogen (N2), etc. into riparian agricultural fields to sustain soil fertility and agricultural productivity. Hence, this phenomenon also impairs the soil fertility of downstream river floodplains and forces the use of larger amounts of artificial fertilizers that only accelerates soil degradation in the long term. On such a note, Bhattarai asserts that the tests and research to acknowledge the impact of river damming projects on the agricultural productivity of the downstream floodplains are largely overdue in Nepal.

Hydroelectricity dam infrastructures in Nepal, nevertheless, are commonly accompanied by settling basins or desilting tanks that capture sediments of the river at the bottom of the desilting tank to ensure that only sediment-free water safe for the generation infrastructure is flown through the penstock. Meanwhile, the sediments settled at the bottom of the tanks are periodically dredged downstream from the dams to get rid of the sediments accumulating in the tank. Although the desilting process may contribute towards flushing trapped sediments downstream from the dam, Kumar believes that the process is visibly ineffective in replicating the natural hydraulics of sediment transport and recapturing the downstream sedimentation flow advantages. Kumar conveys that the uninterrupted flow of sediments in a river system is a delicate process that naturally meets specific flow requirements consistent with the hydrological flow pattern. Hence, this natural fluvial phenomenon cannot be replicated after separating the sediments from the river water while letting the two entities pass downstream with a significant anomaly in time, load, and distribution from their natural pattern.

Issue of fish migration blocking

Apart from sediment entrapment, dams across river systems also block the migratory pattern of fishes that migrate upstream and downstream to fulfill their lifecycle process. For instance, dam structures are known to prevent fish from traveling to their traditional area of spawning and feeding, thus leading to their survival stress. At present, dams in North America are known to have caused disastrous impacts on salmonoid species that traverse between the ocean and rivers following the diadromous migratory pattern. Meanwhile, a report published in the Nepalese Journal of Aquaculture and Fisheries discovers barrages and dams of ROR hydroelectricity projects in Nepal to have impacted the migratory pattern of common endemic species such as Schizothorax (Common snow trout) that migrate in the potamodromous pattern (within the freshwater system) in response to thermal cues and search of food.

Although fish ladders and passages are commonly integrated with the dam infrastructure to let fishes pass through the infrastructural divide, they have often not remained sufficiently effective in allowing fishes of all species or in all stages of the lifecycle that retain differentiated capabilities to negotiate the passage. Adarsha Man Sherchan, a conservation biologist and founder of the Bagmati Biome Project, complains that fishing passages built by dam builders are inconsistent with the migratory pattern, capability, and behavior of endemic fishing species found in river systems in Nepal. More so, the passages are often too high from the downstream river surface and are only usable for fish during the monsoon season when river beds rise to their highest level at par with the height of the dam or fish ladder. A report published by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in 2018 notes that there is a severe absence of baseline information regarding the migratory pattern of endemic fish species in Nepal. And, such has also naturally led fish ladders and passages to remain ineffective in assisting fish migration. The study notes that the separation of the river system by dams with less effective fish passages has disturbed the natural spawning and feeding habit of migratory fishes, led to changes in the composition of upstream and downstream species forming metapopulation structure across the dam infrastructure, and have also caused loss of the species altogether. Meanwhile, Bhattarai notes that conducting a preliminary survey of the status of fisheries and aquatic biodiversity is mandatorily required as part of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) before constructing dams. However, the quality and ingenuity of the assessments are heavily doubted.

Meanwhile, dams are not the only obstacles that deny connectivity, flow, and migration between the stretches of a river system. The significantly reduced flow rate of the river as the result of the diversion of the upstream flow into the penstock also denies passage for endemic migratory fish species to traverse between the river system. Although the environmental provision of the Hydro Power Development Policy of Nepal, 2001 in section 6.1.1 mandates ten percent of the minimum monthly average discharge of the river as instream or environmental flow to ensure sufficient passage for fish migration, dam operators are known to have been popularly compromising the mandate during the dry seasons to secure maximum flow rate for power generation. It has led to the occurrence of dry beds between the intake and outlet sections of the river stretches during dry seasons, thus severing fish migration despite fish ladders being installed at the dam sites. Bhattarai ironically notes that hydroelectricity projects owned and operated by the government are mostly engaged in flouting regulations concerning instream flow regarding which the cascading hydroelectricity projects of the government in the Marsyangdi river can be taken as a classical case. Meanwhile, Kumar recognizes the lack of a proper monitoring mechanism to ensure the enforcement of the instream flow provision by the regulating entity is also the reason behind dam operators to have not taken the regulation seriously in the first place.

The ADB study report, on the other hand, indicates that blanket mandates for environmental flow applicable to all rivers can be insufficient for certain river systems based on the unique ecological characteristics of the regulated rivers. Instead, it recommends environmental flow mandates be determined by scientific studies depending on the type of fish, local ecosystem, and river gradient. On the contrary, Bhattarai informs that the current regulation requires dam operators to also maintain the level of instream flow as directed in their respective Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report based on the unique ecological and anthropogenic characteristics governing the river system on top of a minimum ten percent mandate. Hence, the issue seems to majorly originate from the weakness in the implementation of the regulation than due to lack of it.

Concluding Remarks

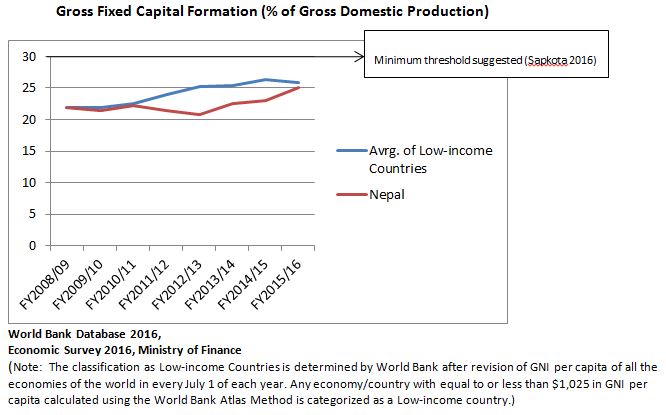

The hydropower industry of Nepal is currently in the phase of developing larger reservoir-type projects with higher installed capacity as it follows the aspiration of the federal government to ramp up the total generation capacity of the industry by more than five folds before the end of this decade. Hence, larger reservoir or storage-type projects such as the 1200-MW Budi Gandaki Hydroelectricity Project and 750-MW Upper Seti Storage Hydroelectricity Project have surfaced in the list of national pride projects of Nepal.

Technically, the development of reservoir-type projects will help the industry leapfrog its hydroelectricity generation capacity and create a portfolio of projects that do not need to rely on the natural flow rate of rivers for power generation. However, forming large reservoirs behind dams in lower geological regions with sufficient flat lands to submerge will directly expose the industry to a range of adverse ecological issues concerning reservoir systems and significantly escalate tensions with local riparian communities as reservoirs shall claim significant portions of the upstream riverine habitats. In such context, the 40-km long reservoir system of the pledged Budi Gandaki Hydroelectricity Project (BGHEP) is already expected to displace 50,000 people of the local community and submerge a substantial area of ecological, agricultural, and cultural significance. But visible lapse remains in the capacity of the governments in Nepal to arrange compensation and resettlement plan suitable for the affected communities. An academic thesis on Development-forced Displacement and Resettlement (DSDR) in Nepal notes multiple political and social challenges for arranging compensation and resettlement needs for habitat and livelihood impacts resulting from large dam constructions. In the meantime, marginal communities settling on unregistered lands and relying on common natural resources such as rangelands, local water bodies, and forest products for socio-economic livelihood fall into the risk of not being properly aided and left in despair if such land covers are inundated.

Transitioning to the phase of mega hydroelectricity projects in Nepal with taller dams and larger reservoir systems in lower geological belts of the country also calls for the hydropower industry, its regulators, and the larger stakeholders to expect severe ecological impacts across the length of the river systems that naturally follow such developments. As such, it is time that the hydropower industry largely contributed towards conducting a comprehensive study of the dynamics of the hydrosphere, biosphere, and cryosphere of the transboundary river basins flowing through the landscape of Nepal to significantly acknowledge, model, and estimate the nature of impacts that will result into such domains from the expedited development of large dam projects in Nepal. Such baseline studies shall particularly help the power producers to take precautionary measures to limit the anticipated impacts, and conduct periodic monitoring of the impact to acknowledge its severity. At present, ICIMOD studies conducted under the Koshi Basin Initiative (KBI) serves as a notable reference portal to initiate such basin-level assessments also in respect to the development of hydroelectricity project in the watersheds of the respective basins. Meanwhile, Kumar confirms that the Water and Energy Commission Secretariat (WECS) of the federal government is already initiating basin-level studies that touch upon the needed scope of assessments.

Apart from establishing astute regulatory arrangements for environmental assessment and monitoring of dam impacts, Kumar claims that a paradigm shift is also required in the organizational culture of the hydropower industry in Nepal which is yet to support improvement and innovation in the field of environmental assessment to initiate novel tests to acknowledge previously undiscovered ecological or social impacts of dam construction. At present, the industry needs to develop sufficient flexibility and agility to continuously experiment with novel assessments and tests that are outside the conventional mandates for it to become proactive in researching, preempting, and mitigating the wider social and ecological implications of larger hydroelectricity projects in Nepal.