This paper redirects the scope of my previous compilation paper (Collaboration Paper: What actually guides inflation scenario in Nepal) that attempted to constitute multiple viewpoints on factors that are significant in determining contemporary inflation scenario in Nepal. The previous paper concentrated on Indian inflation transmission and monetary policy transmission to enquire the significance of Indian inflation (in respect to fixed-pegged exchange rate and voluminous trade activity) and domestic monetary policy measures over the Nepalese inflation scenario. On the other hand, this paper redirects the overall inquiry towards acknowledging the role of supply-side constraint (supply shock or disturbances) towards the contemporary inflation scenario in Nepal.

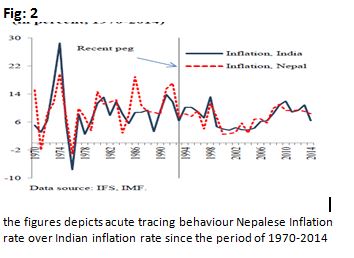

The quest or the inquiry of identifying the role of supply-side variables in determining the contemporary period of running inflation can always start with the study of the mechanism of Indian inflation transmission towards the Nepalese inflation scenario. Though the law of one price of the theory of Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) in the event of fixed peg regime would warrant virtually complete price-taking behavior of the smaller economy from the larger trading economy (Ginting, 2007), Dobrescu, Nelmes, & Yu (2011) observes strong deviation of Nepalese inflation scenario from Indian inflation scenario since the period of 2007/2008 even when the condition for law of one price remained. As Dobrescu, Nelmes, & Yu (2011) observed in Fig 1, the upward escalation of the Nepalese inflation scenario against the Indian inflation scenario since 2007 was spectacular, and the upward escalation difference of Nepal-India food price inflation quadrupled in compared to analogous escalation difference in the non-food price difference.

In explaining the observed departure from the constraint of law of one price given the fact that Nepal fulfills the condition of being a small open economy having fixed exchange peg regime with a larger Indian economy from whom the import trade activity is voluminous, one has to consider the limitation of the theory of PPP itself that derives this very law. While multiple approaches have already questioned the ignorance of PPP theory regarding the influence of non-tradable factors in its law of one price, the theory also appears to be undermining the influence of persevering temporary domestic shocks (v) that can effectively disturb the pass-through of inflation rate even in the fulfillment of required conditions (Ginting, 2007). In fact, the interplay of one or both of these undermined variables could be the reason behind the observed deviation in the Indo-Nepalese Inflation scenario in Fig 1 causing inflation overshoot in Nepalese economy (especially on food-price).

In respect to that, while Ginting (2007) observes long-term converging relationship of core-inflation in Nepal (inflation measure excluding factors of strong temporary volatility and shocks) with Headline inflation of India (unadjusted inflation measure), he logically assumes the role of temporary shocks (v) originating from Nepal to contribute towards deviation in Indian and Nepalese headline inflation. As Ginting (2007) comes to this finding after conducting ADF test on relevant dataset from the period of 1996 to 2006, the observed deviation in Fig 1 can be relevantly regarded as a figurative proxy of Ginting’s finding of deviating Indo-Nepalese headline inflation due to temporary supply-shocks originating from Nepal itself. In fact, the figurative proxy (i.e., Fig 1) that accounts dataset from 2001-2011 also depicts strengthening magnitude of Indo-Nepalese headline inflation deviation exposing larger role of so-called temporary supply-shock (disturbances) in persistently causing headline inflation overshoot (especially in food-price) in Nepal since 2007. Importantly, as the enquiry of Ginting (2007) with data limit until 2006 was not suggestive of this portion of the figurative proxy (i.e., Fig 1) that observes dramatic persistent influence of this so-called temporary supply shock since 2007, he believed the temporary shocks to evaporate in the long-run, thus boiling down to acute Inflation convergence of India and Nepal in the long-run.

Subsequently, Sapkota (2011) disregards the guiding principle of Ginting (2007) finding that regards the headline inflation deviating temporary supply-shock factors (v) to not prevail in the long-run. While Sapkota (2011) acknowledges the role of temporary supply-shock factors (v) in causing Indo-Nepalese headline price deviation, he also argues over the persistency of these so-called temporary supply shock factors (v) since the period of 2007/08 that observed temporary rise in International Oil-food-commodities price. Ultimately, Sapkota (2011) conforms to figurative proxy (i.e., Fig 1) exposing the role of persistent supply-shock (or disturbance) in gradually strengthening the magnitude of Indo-Nepalese headline inflation deviation and causing Nepalese Inflation overshoot since 2007/08. In fact, Sapkota (2011) further regards supply-disrupting activities (factors) as

- Black-marketeering

- Supply-hoarding on irrational inflation expectation

- Conducting public strikes and

- Creating difficulties at Custom points from India’s side

to be the reason behind occurred long-run stickiness of the price level on the high ground even though the price level was supposed to fall back following the cooldown of temporary rise in International oil-food-commodities price rise sometimes after 2008. In a nutshell, the disturbing activities (factors) noted by Sapkota (2011) appear to be non-economic in nature and therefore can be beyond the realm of fiscal or monetary policy.

On contrary to overall findings observing the deviation in Indo-Nepalese headline inflation, the findings of Budha (2015) observers Inflation pass-through from Indian Inflation scenario to Nepalese inflation scenario in the period of 4-8 months (i.e., rate of 7-12pc convergence each month) in his observation of price-levels from the period of 1994 to 2014.

In alike to the findings of Budha (2015), Dobrescu, Nelmes, & Yu (2011) in their separate Vector Auto-regression (VAR) analysis of full-dataset ranging from 2000-2011 and partial dataset ranging from 2007-2011 (signifying event after 2007) also observed strong influence of India’s inflation and International oil price movement in determining Nepal’s inflation scenario (see Fig 3a and 3b). While these two factors were accounted to be responsible for more than 1/3 of the Nepal’s inflation variability, International Oil price movement was reckoned to reserve stronger influence in Nepal’s inflation variability mainly after 2007 (Dobrescu, Nelmes, & Yu, 2011) (see Fig 3b). However, although recognizing the significant influence of Indian inflation and International oil price movement in Nepal’s inflation variability, the significance of Supply-side shock (v) in determining the current inflation scenario in Nepal cannot be undermined at all. After all, the significant drop in Brent Crude Oil price Index by more than 50pc during the mid of 2015 until the beginning of 2016 didn’t exert much cooling impression in Nepal’s inflation scenario that was already wrestling with different forms of supply-shocks (v) (Trading economics, 2016).

As the implication of Supply-side shock (v) on Nepal’s current inflation scenario is discussed while accounting for renowned influencing economic variables as Indian Inflation transmission and International Oil price movement, it is also very important to test this implication while acknowledging the demand-side economics. As, it is another significant economic variable vibrantly guiding the inflation scenario in developed economies.

In acknowledging Sapkota (2010), he doesn’t observe much influence of Domestic demand-side factor in determining the inflation scenario in Nepal. Elaborately, he doesn’t see the significance of sparse volatility in domestic private Investment Expenditure (I), Net Export (NX) in along with stagnancy of domestic consumption expenditure (C) accounting for 90 pcs of GDP since last five years (before 2010) in determining the past volatile inflation scenario in Nepal. Therefore, given the lack of correlation in past trend, it may not be accurate to hold domestic demand-side factor strongly responsible for observed headline Indo-Nepalese inflation deviation or current inflation scenario in Nepal since 2007/08. However, given the fear of Sapkota (2016) of government policy being unable to suppress the inflation rate to 7.5pc in eventuation of jumbo NRs 1 trillion worth National budget, the upward pressuring potential of Demand-side economics over Nepal Inflation scenario cannot be ignored in near future. But again, it still doesn’t challenge the logic behind the strong perseverance of supply-shock (v) in guiding Nepal’s running inflation scenario.

Now that we have tested and approved the persistence and impact of should-be short-run temporary volatility (supply shock or disturbance) (v) on Nepal’s running Inflation scenario after acknowledging various influential economic factors (i.e., Indian Inflation transmission, International Oil price movement, and Demand-side pressure), observation of tools and techniques that can eliminate this non-core inflationary pressure needs to be studied as well.

Having said, monetary policy transmission or adjustment is recognized to be an important nominal tool in doctoring the inflation scenario of an economy as it often deployed by central banks all over the world in meeting their preferred macroeconomic target or to stabilize the economy. Federal Reserve Bank of America, Bank of Japan (BOJ), and European Central Bank (ECB) are prominently renowned in deploying their monetary arsenals in stabilizing their respective sophisticated economy by mostly manipulating interest rates to adjust inflation rate. While prominent economist Milton Friedman also argues Inflation rate to be a complete monetary phenomenon, Roger (1997) instead emphasizes the constraint of monetary authority to only influence the core-inflation scenario but not the temporary shock factors (or persistent temporary supply shocks in case of Nepal). And it happened to be so that the finding of this paper observed major role of persistent temporary supply shock in guiding Nepal’s running inflation scenario. Therefore, on subscribing to logic of Roger (1997), Nepal’s central monetary authority (i.e., Nepal Rastrya Bank (NRB)) has highly limited ability to dictate the Nepal’s contemporary inflation scenario.

Sapkota (2009) also regards the contemporary running headline inflation of Nepal to be completely outside the boundary of traditional monetary instruments at the disposal of the central bank. As Sapkota also maintains strong argument regarding the role of persistent supply-shock incidence (or disturbances that appears non-economic) as the major culprit to Nepal’s running headline inflation, he doesn’t find any remedy to this issue through the vault of monetary arsenals that is limited to realm of economics. In fact, he instead proposes an array of political, legal, regulatory and diplomatic measures to counter this issue. Statistically, Sapkota (2010) observes random regression between M2 growth (a proxy of monetary policy) and Inflation behavior in Nepal since the past decades in Fig 4.

In alike to Sapkota’s consideration, Ginting (2007) also disregards the effectiveness of monetary measures in countering the temporary shock factors that he observes to be disturbing the convergence of headline inflation between Nepal and India on his own ADF test of relevant variable from 1996-2006. His paper however remains silent regarding the effectiveness of monetary policy transmission in Nepal.

On the contrary regarding the ineffectiveness of monetary policy in countering Nepal’s headline inflation overshoot, Dobrescu, Nelmes, & Yu (2011) on their VAR analysis of full dataset ranging from 2000 to 2011 observes short but strong influence of Broad Money (M2) in Nepal’s non-food price inflation (see Fig 5). Given the fact that they also observe almost similar influence of Broad Money (M2) in Nepal’s food price inflation, they encourage intense role of Nepal Rastrya Bank (NRB) in curbing and adjusting Nepal’s inflation scenario in oppose to Sapkota (2009) and Ginting (2007).

Likewise, Budha (2015) also finds impressive ability of his identified independent Nepalese Monetary policy to influence the inflation scenario of Nepal. After all, he identifies the role of expansionary monetary policy to let CPI of Nepal reach its peak level at 6th quarter after which the effect totally fades out by 10th quarter.

Conclusion:

As the paper tested the persistent role of supply-side constraint in determining Nepal’s running inflation scenario while acknowledging other significant economic phenomenon as Indian inflation transmission, International Oil price movement, and demand-side economics, it comes to its approval, and therefore its presence. Again, in concern to it after considering various past papers (Sapkota (2009, 2010, 2011) & Ginting (2007)), the recommended resolution to this issue of price-level stickiness on high ground has mostly been non-monetary measures relating to political, regulatory and diplomatic avenues.

However, the observed independence of Nepalese Monetary Authority and influence of domestic monetary operations on Nepal’s CPI in couple of past papers (Budha (2015) & Dobrescu, Nelmes, & Yu (2011)) signals necessity to reconsider the deployment of available monetary arsenal of Nepal Rastrya Bank on specifically countering inflation overshoot. Especially, if the potential monetary policy transmission of the observed monetary independence has any implication over the core-victims of food-price inflation (i.e., the poor & deprived ones). And, also if the food-price inflation can be linked to the rise in price of urban non-tradable factors (i.e., rent, building & land prices) known to be caused by demand-side pressure.

Keeping aside everything else, just in acknowledging the finding of Asian Development Bank (ADB) regarding the ability of 20pc food price inflation in Nepal to increase the poor population by more than 1 million, (i.e., 4 percentage points increase in poverty ratio), the purpose to research on political, regulatory and economic policies & avenues to counter this unnaturally rising inflation having strong hit on food-prices seems urgent.

References:

Dobrescu, G., Nelmes, J., & Yu, J. (2011, September 26). Inflation Dynamics in Nepal. International Monetary Fund Nepal, 2-8. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

Budha, B.B. (2015). Monetary policy transmission in Nepal. NRB Working Paper No. 29. Nepal Rastrya Bank

Ginting.E. (2007). Is inflation in India attractor of Inflation in Nepal? IMF Working Paper WP/07/269. International Monetary Fund.

Sapkota, C. (2011). The Source of Food and Non-food Inflation in Nepal. Accessed from:http://sapkotac.blogspot.jp/2011/11/sources-of-food-and-nonfood-inflation.html

Sapkota, C. (2010). Will Nepal’s fiscal budget 2010-2011 increase inflation? Accessed from:http://sapkotac.blogspot.com/2010/12/will-nepals-fiscal-budget-2010-2011.html

Sapkota, C. (2009). Sticky inflation and policy option for Nepal. Accessed from:http://sapkotac.blogspot.com/2009/08/sticky-inflation-and-policy-options-for.html

Sapkota, C. (2016). Budget Blues. The Kathmandu Post. Accessed from:http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/news/2016-06-17/budget-blues.html